OI #2: Lucky Number

Here’s the problem statement; it’s again written in Chinese so here’s the English summary. You’re given a tree with nodes which each have a value written on them. You must answer queries which each ask, for a given simple path between two nodes and , what is the maximum value that can be formed by XOR-ing values of nodes along that path (including and )?

XOR Basis

The core of this problem is the following: given a set of numbers, how can I find the maximum XOR of any subset of these numbers? Here’s a great Stack Exchange article about this problem, but I urge you to read through this article first and consult the Stack Exchange article only if you get stuck.

To start, let’s consider a reduced subproblem. Define the dimension of a number to be the position of its highest bit. How can we solve this problem if our set contains at most one number in each dimension? (Again, the answer is in the Stack Exchange article, but I urge you to think it through yourself first.)

Once we’ve figured that out, we just need a way to somehow reduce our set to a set which satisfies this condition. More formally, define the span of our set to be the set of all possible XORs of its subsets: we wish to find a set with the same span, but which contains at most one number in each dimension.

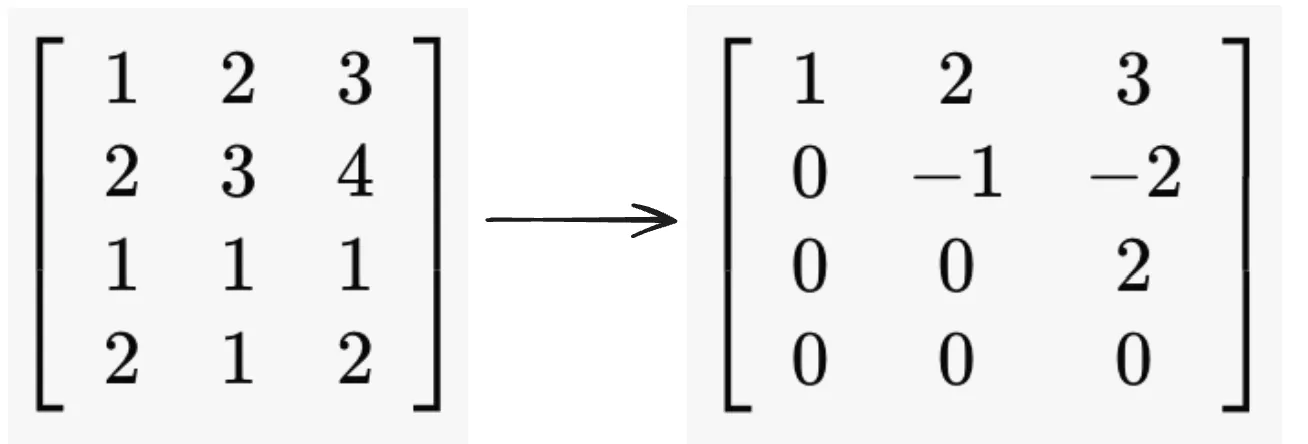

The linear algebra terminology is deliberate, as this idea of “eliminating” dimensional redundancy is at the core of Gaussian elimination. Although its most well-known application is to solve systems of linear equations, what we care about here is its ability to convert a matrix (i.e. a set of vectors) into row-echelon form, which is exactly what our condition is describing: a set of vectors, with at most one vector in each dimension.

A matrix and its row-echelon form. Verify that the row space (span of the row vectors) of both matrices are the same, and that the row-echelon matrix has only one vector in each dimension.

To make this concrete, let’s step away from XOR for a second and think about how this process works in linear space. Say we have the 3 vectors . We can “reduce” this set by picking one 3D vector—say, —and “eliminating” the others with it. For instance, consider the span of and , which consists vectors of the form , where and are arbitrary scalars. However, we can rewrite this as

Which is just the span of and . Therefore, we can “reduce” to : this, not solving systems of equations, is the core idea of Gaussian elimination. Now, see if you can apply this method to reducing bit-vectors under XOR!

Closing Thoughts

The rest of the problem is pretty fun and simple, so I’ll leave it to you as an exercise. This problem is the first time I’ve encountered the idea of XOR basis, so I thought it would be nice to write this little blog about it!

That’s it for this problem; As always, here’s my submission in case you get stuck.